First, congratulations! You just made a decision: to click on this blog post. That choice likely happened subconsciously. Maybe the headline caught your attention, or perhaps curiosity led you here. Either way, your brain may have made the decision before you even realized it. And it doesn’t stop there. Think about your current posture, your last meal, or what you’re wearing today. Each of these is the result of a decision. Sometimes active, sometimes passive, but most often subconscious. But have you ever made the decisions to think about how decisions are made? If not, here’s your chance.

Our brain is an incredibly efficient processor, often compared to a computer’s processing unit. Both handle vast amounts of information with remarkable performance. However, despite its complexity, the human brain likely consumes far less energy than a conventional computer (there are reports that the brain takes only 20 watts of power). Unlike computers, where every process can theoretically be understood, the brain remains largely a mystery. While we have insights into brain regions, their connections, and communication pathways, the exact mechanisms behind real-world problem-solving are still not fully understood. Decision-making is one of the brain’s core functions, extending far beyond simple A-or-B choices. Before making a decision, we first need to recognize something as a problem, determine a desired outcome, and evaluate potential solutions. Remarkably, most of these steps happen almost instantaneously! Studies suggests that we make around 30,000–35,000 decisions per day, and more than 200 of them are solely related to your meal. Yet, the majority of these decisions occur subconsciously, without us even realizing it.

Complex brain for intuitive decisions?

A decision can be understood as the selection of the best option from a choice set containing two or more alternatives (Beach., 1993), motivated by overarching goals. However, not all decisions follow strict logic or deep reasoning. Instead, behaviour and choices often rely on heuristics, which are mental shortcuts, conscious or unconscious, that provide solutions that are good enough (Gigerenzer et al., 2011). Heuristic reasoning typically comes into play when individuals must act quickly or navigate multiple competing goals (Gigerenzer, 2008). There are multiple heuristics, one well-known example being the availability heuristic. This heuristic is often applied unconsciously when humans need to assess the importance or frequency of an event under time pressure or when precise statistical data is unavailable. In such cases, judgments are influenced by how easily similar events come to mind. Events that are more readily recalled tend to be perceived as more probable than those that are harder to remember. The problem is that outcomes potentially leading to biased or incorrect conclusions. While heuristics can be efficient in everyday decision-making, they may pose significant risks in safety-critical environments such as aviation. In such contexts, reliance on heuristic decision-making can lead to bad decisions with potentially severe consequences.

Option A or B or something else?

Some decisions are easy and made quickly (do I take a spoon or a fork for the soup?). Others require a bit more thought (am I in the mood for pasta or a salad?). And then there are decisions that are trickier. What happens when a situation doesn’t present a clear right or wrong choice, but rather, each option comes with its own advantages and disadvantages? If you’re under time pressure to make the best possible decision, the challenge quickly escalates into a stressful task. In aviation, such situations can arise rapidly, with safety always being the primary concern.

Let’s consider a fictional emergency scenario: You’re a pilot flying over the Atlantic when you receive a report that a passenger is showing symptoms of a heart attack and requires urgent medical attention. Your onboard resources are limited, so landing as soon as possible is crucial. Your planned destination is still hours away. There is an alternate airport just a few minutes away, but the weather report warns of strong winds and heavy snow, making the landing potentially hazardous. A third airport is slightly farther away, with good weather conditions but limited medical infrastructure, posing a risk to the patient’s health. Ask yourself, how would you decide?

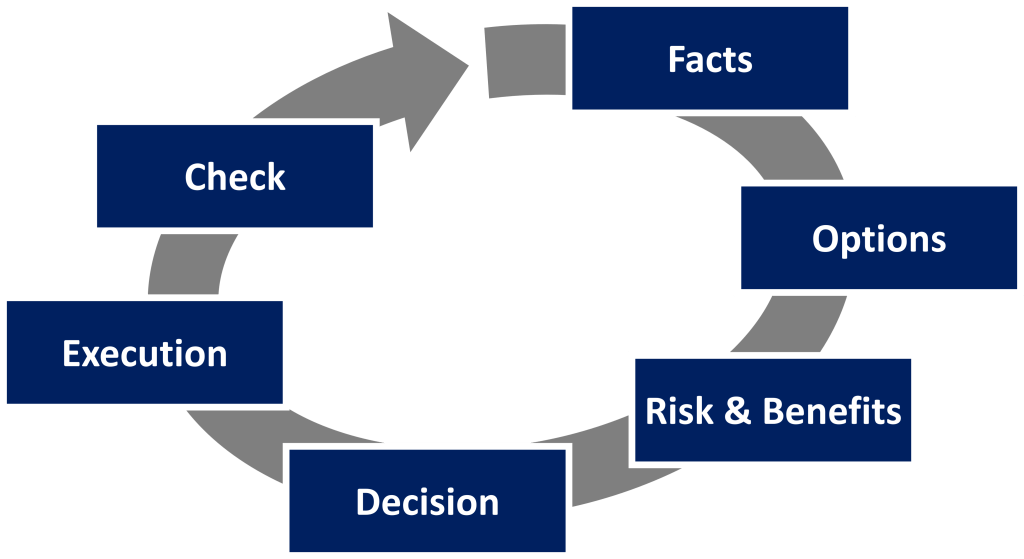

Of course, this is a hypothetical example, but it illustrates the complexity and ambiguity of decision-making in aviation. Pilots operate in teams, and no critical decision should be made without consulting the other pilot. This principle is central to Crew Resource Management (CRM), which focuses on optimizing available resources to enhance safety. CRM includes cross-monitoring, mutual support, effective communication, task delegation, and joint decision-making. To structure and formalize decision-making, especially in critical situations, models such as FORDEC have been developed. This acronym represents a structured approach to decision-making:

- Facts: Identify and list the key facts of the situation. What is the nature of the emergency?

- Options: Evaluate the possible courses of action. What choices are available?

- Risk and Benefits: Assess the risks and benefits of each option. What are the pros and cons of flying to Airport A versus Airport B?

- Decision: Make an active and informed decision based on the analysis.

- Execution: Implement the chosen course of action.

- Check: Monitor the outcome: Does the decision work as intended? If the situation changes, should the plan be adjusted?

By following structured decision-making models like FORDEC, pilots can ensure that even under pressure, decisions are made systematically, with safety as the top priority. FORDEC can be applied in different ways. In non-time-critical situations, the entire FORDEC process can be followed step by step to identify the best possible solution. However, in time-critical situations, FORDEC can help to quickly identify the first suitable solution. Structured decision-making significantly improves outcomes and decision quality by reducing the influence of heuristics, biases, and other cognitive traps.

Given the immense processing power of our brain, it almost seems paradoxical that heuristics and biases exist. Don’t they limit our decision-making performance? Or is it rather the other way around? Perhaps we owe our high cognitive efficiency to heuristics, as they allow us to process information rapidly and effectively.

References

Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Why heuristics work. Perspectives on psychological science, 3(1), 20-29.

Gigerenzer, G., & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual review of psychology, 62(2011), 451-482.

Beach, L. R. (1993). Broadening the Definition of Decision Making: The Role of Prechoice Screening of Options. Psychological Science, 4(4), 215-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00264.x