Safety is always expected when flying, but rarely considered by passengers. It is something everybody wants, yet no one can fully guarantee. The aviation industry works extensively to enhance safety, and today, the chance of being involved in a fatal aircraft accident (per flight hour) is 0.000000001. In other words, the likelihood of a catastrophic aircraft failure is just one in a billion flight hours. To put this into perspective, the odds of being struck by lightning in a given year are less than one in a million.

We dream of a world without accidents, incidents, or any kind of trouble – and that is fully understandable. Any aircraft disaster that results in loss of life is tragic and should never happen. But if we take a moment to reflect, how far have we actually come? In the course of the development of modern aviation over the last 100 years, there have been numerous near misses and tragic accidents. Initially, it was mainly technical faults, but later humans were also identified as a contributory factor – the birth of human factors research. Mankind desperately wanted to fly, reliably and safely. Thus, the aviation industry managed to understand the “why” behind many accidents, improving technical and human reliability. But was all this necessary? Could it be that a certain degree of un-safety was or is necessary to achieve greater safety?

Let’s go out on a hike

Imagine you are hiking on a well-marked mountain trail. The path is clear, the weather is perfect, and you are feeling confident. To add a little excitement, you decide to step off the trail now and then, maybe to snap a photo of a beautiful wildflower. At first, it seems harmless. The trail is still in sight, and you are only a few steps away. But as you keep hiking, these small detours become a habit. Each time, you wander slightly farther from the trail. A few more feet to explore a rocky spot. The terrain starts to look rougher, but you don’t panic. After all, you are still close enough to hear other hikers, and the trail is just over there. After some time, the sky clouds over. The trail makers become harder to spot. Oh no! You suddenly realize, you are standing in the thicket of bushes. And which direction should you go to come back? The phones battery drained out and no trail is in sight. What began as tiny, reasonable risks has left you stranded in a dangerous situation.

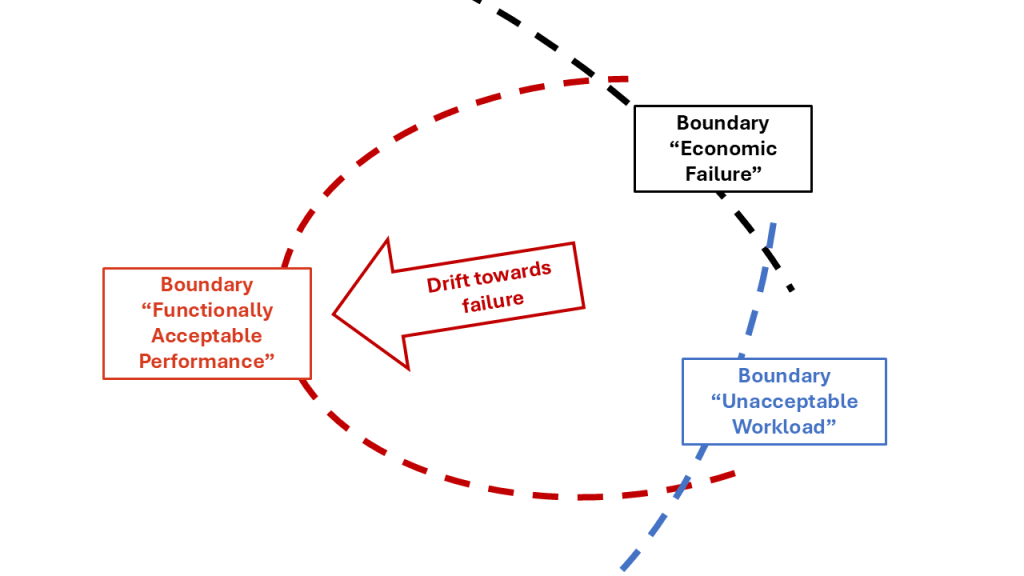

We can try to transfer that example to socio-technical systems and aviation. Rasmussen’s drift-to-danger model (1997) describes how human behavior and decision-making in safety-critical industries fluctuate within certain boundaries. Decisions and actions of systems and operators are based on several factors. There are safety margins, which influence behavior. But other pressures are there as well. Management often pushes for increased efficiency, placing pressure on workers to maximize output (economic failure boundary), while individuals may also be motivated by the principle of minimum effort (unacceptable workload boundary). That does not mean that people are lazy. Let us say humans want to work as efficiently as possible. Work overload is something to be avoided. And the model postulates that as long as we stay within these boundaries, we are safe. But what if we stretch these boundaries? And what if we even overstretch the boundaries? As a result, there is usually a drift towards the third boundary: the functionally acceptable performance. In other words: safety. If this boundary is breached, safety can be compromised.

When being on a hike and making detour, this describes the stretch. It describes the drift to danger:

- Small, seemingly safe decisions: Each detour felt minor. You just step off for a second.

- No immediate consequences: Nothing bad happened at first. You kept pushing the boundaries.

- Crisis sneaks up: By the time you realized the danger (got lost, bad weather), it was already too late.

Back into the bushes. After a while, a ranger comes into view. She tells you that this often happens and that she makes extra rounds through the countryside to look for stranded hikers. Together you find your way back to the path.

So, what does this mean for aviation and safe systems? To put it briefly: we need a resilient system. Resilience is a measure of a system’s ability to absorb continuous and unpredictable change and still maintain its vital functions (Pregenzer, 2011). In this context, resilience is the ability of an organization and a system to anticipate when these safety limits are in danger of being exceeded and to take countermeasures. Resilient systems are characterized by a heightened awareness of unexpected situations and the ability to develop strategies to mitigate them (Hollnagel, Woods, & Leveson, 2006).

That was close

After a few days of reflection, you understand what caused you to get stranded. You realize how dangerous it was. And you decide that you won’t do it again. Next time you’ll stay on the path, that’s the lesson you’ve learned. But would you have been able to recognize that without the event?

Many accidents cannot be predicted due to the high complexity of systems and unforeseen system states. Ironically, it is often these very accidents that reveal a systems weakness. Do we then have to live with accidents to discover the weaknesses? Well, yes and no. Probably we cannot avoid every accident. But we can do something proactive. Accidents rarely happen without warning. There are usually precursors: unusual system states, error messages, minor incidents or even bad feelings of the human. Those signal potential system issues and perhaps even predict incidents. Thus, it is crucial for organizations to recognize and investigate these warning signs. This responsibility typically falls to the safety department, which carefully analyses incidents and even the slightest deviations to identify risks before they escalate. With that, resilient systems can be shaped.

All of this goes unnoticed by passengers, but safety should never be taken for granted. The next time there is a delay due to a technical check or a procedural disruption, remember that these measures are taken for safety. Every precaution, no matter how small, is part of a system designed to prevent accidents before they happen. And remember, in aviation, these measures are often the result of incidents or even accidents.

References

Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Why heuristics work. Perspectives on psychological science, 3(1), 20-29.

Gigerenzer, G., & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual review of psychology, 62(2011), 451-482.

Beach, L. R. (1993). Broadening the Definition of Decision Making: The Role of Prechoice Screening of Options. Psychological Science, 4(4), 215-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00264.x