Twinkle, twinkle, lite star… No, wait… not now! It is 3 AM, my coffee is gone cold, and my brain feels like static – welcome to the night shift grind!

Our modern society requires people to work at inconvenient times. Early in the morning, late in the evening or throughout the night. But there is no other choice: air traffic has to be monitored at night, and if an early departure is scheduled, pilots have to check in at 4 a.m. to prepare the airplane.

Working at night is risky. That is more or less cold coffee now. But are all shifts similarly demanding? And what can be done? We will explore night work and talk about strategies. And why kiwi fruit may be more relevant than you think.

We are Owls or Larks (or something in between)

Humans are biphasic. We either are awake or sleep. During a 24-hour cycle we require a distinct sleep when not being in wake phase. The timing of the sleep phase seems to matter as well. In research, there is common understanding that work during the night time seems to be associated with risks.

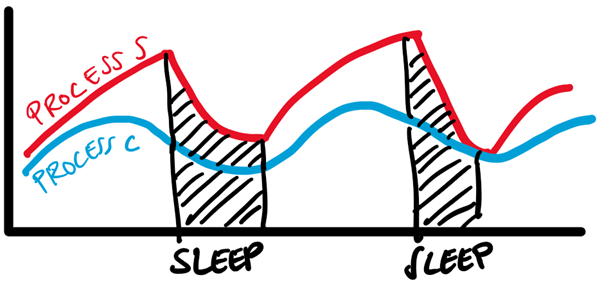

A night shift cannot be viewed separately. It must be portrait in regards to many other aspects, such as sleep during the last days, physical activity and chronotype. During a given night shift, sleepiness and fatigue can be also product of our inner circadian rhythm. The circadian rhythm is our inner clock that drives many of our physiological processes. That includes the release of hormones, onset of sleepiness and sleep. Two distinct biological processes interact to regulate sleep and wakefulness: Process S and Process C (Borbély, 1982). Process S (red line in graph below) is like a “fatigue tank” in your body. The longer you are awake during the day, the more this tank fills up – you become sleepy. At night, while you sleep, the tank empties again. This refers to the sleep-wake homeostasis, representing the physiological drive for sleep, which accumulates during wakefulness and dissipates during sleep. Process C (blue line in graph below) is your internal clock, which ticks independently of the pressure of sleep. It tells you in the evening: “Time to sleep!”, even if your “fatigue tank” is not full. It wakes you up in the morning, even if the tank is not yet completely empty. This refers to the circadian rhythm, which governs the timing of sleepiness and wakefulness over a 24-hour cycle, independent of sleep debt.

Both processes interact with each other. During the day, Process C keeps you awake, even when sleep pressure (S) rises. In the evening, Process C triggers the need for sleep, while Process S empties the “tank”. Problems such as jet lag arise when the internal clock (C) does not adjust quickly. Sleep deprivation occurs when the “tank” (S) is not emptied enough.

And what is the deal with owls and larks? This refers to our chronotype, i.e. our body’s natural tendency to be asleep or awake at a certain time. In other words, it is the behavioural manifestation of the underlying circadian rhythm. You may have met people who like to get up early in the morning and go to bed early at night – congratulations, you have just met a lark (or rather a person with a morning chronotype)! And then, of course, there are those who like to get up late in the morning after going to bed late at night. These are the owls, that means people with an evening chronotype. Perhaps you see yourself somewhere in between. But that is fairly normal as most people are actually intermediate chronotypes, falling into a category somewhere in between.

Are All (Night) Shifts Equally Challenging?

Let’s be clear: The human is not made for night work. Night shifts are and will always be a challenge that is associated with risks. Shift and (night) work is inherently associated with an increased risk to physical and mental health, reduced safety, a poorer social life and lower work performance. So, are all night shifts equally demanding? No, of course not. A lot depends on your genetic predispositions, your sleep and your work experience. The shift schedules you work play an important role. Rotating shifts disrupt the circadian rhythm much more than fixed shifts (Folkard & Tucker, 2003). Individual differences between us moderate tolerance to shift work and night shifts. Personality and some genetic predispositions have been found to be related to higher tolerance to shift work (Saksvik et al., 2011).

Survival Strategies: What Actually Works?

According to most researchers, the most effective strategy for overcoming the negative effects of night shifts is a nap. Napping refers to short sleep opportunities of 20 to 40 minutes. It seems to be optimal if the napping episodes are scheduled during the work shift, e.g. with the help of napping programs (Ruggiero et al., 2013). If night work is considered in a broader context, the influence of (day) light should be taken into account. The circadian rhythm synchronizes with daylight. Night shifts disrupt it, but it is possible to adapt: If night work is planned, the circadian rhythm can be adjusted. Remember that your body clock is stubborn – it changes very slowly (think days or weeks, not hours). Thus, light as intervention needs to be used very strategically.

And what is with the Kiwi?

From a night worker’s perspective, kiwi fruit can be a superfood! Kiwis are rich in serotonin and antioxidants, which have been linked to improved sleep quality. But that’s not all. One study found that eating kiwifruit improved the onset and duration of sleep (Lin et al., 2011). So why not consider a kiwi snack before your next sleep episode? Of course, there are many aspects to consider when working shifts, and eating just one kiwi a day is unlikely to help and solve the challenges entirely.

But next time you are staring at the 3 AM void, remember: science can help to save your shift (and to make another fresh coffee).

References

Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Why heuristics work. Perspectives on psychological science, 3(1), 20-29.

Gigerenzer, G., & Gaissmaier, W. (2011). Heuristic decision making. Annual review of psychology, 62(2011), 451-482.

Beach, L. R. (1993). Broadening the Definition of Decision Making: The Role of Prechoice Screening of Options. Psychological Science, 4(4), 215-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00264.x